“Kids Are Hard Work” — But Do They Need to Be This Hard?

A cultural audit of helplessness, trust, and the myth of modern fragility.

Yes — raising kids is hard work.

Most of what exhausts modern parents in the West isn’t innate to childhood. It’s self-inflicted. We’ve built a culture that disables by design. We hover, overprotect, sanitize — and then ask why our kids can’t do anything and our chores just keep piling up.

Take a step back:

Toddlers aren’t trusted to pour their own water.

Five-year-olds can’t cut their own food.

Six-year-olds haven’t made a sandwich, folded laundry, or fed a pet.

This isn’t care. It’s containment via infantilization.

We’ve replaced real contribution with dependence dressed up as nurturing — then wonder why parenting feels like managing a helpless, ungrateful roommate.

The Hard Truth

Kids aren’t exhausting because they’re incapable.

They’re more exhausting in the West because we treat them like they are.

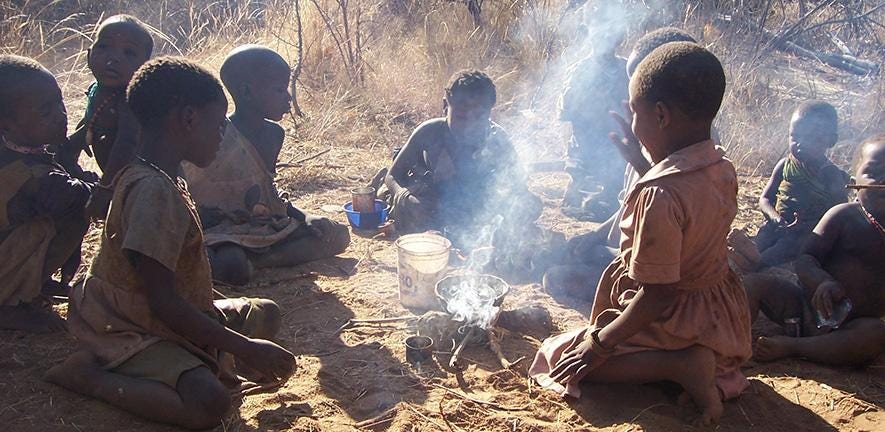

Across most of human history — and in many cultures today — 3-year-olds:

Cook and clean

Tend animals

Care for siblings

Gather food and water

Run errands — solo

These aren’t token chores. They’re real, necessary, and respected contributions. Children don’t beg to help because they’re cute. They do it because they want to matter.

But instead of letting them, we shut them out, slow them down, or hand them a plastic replica of the real thing.

And then we complain they don’t help.

Change the Question

Don’t ask:

“Why are kids so much work?”

Ask:

“What work are they already capable of — if I trusted them?”

The issue isn’t the number of children.

It’s the number of low expectations.

What 3-Year-Olds Actually Do — Globally, and Without a Grown-Up

These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real children, doing real tasks — solo.

In Northern Kenya, 3-year-olds carry water jugs barefoot over rugged terrain —sometimes a kilometer or more away.

In Peru and Bolivia, they gather edible plants, herbs, or fire-starting twigs — without adults nearby.

In the Philippines, they’re sent with coins to buy onions, salt, or snacks from local stalls.

In Papua New Guinea, they stir food over open flame, clean tools, and scrape rust off knives.

In Guatemala, they wash dishes, carry gourds of water on their heads, and rock infants to sleep.

In Mexico, they sweep yards, pluck chickens, and return home with tortillas from the store.

In the Andes, they feed pigs, leash chickens, and guard livestock from wandering too far.

These children use knives.

They manage fire.

They tend animals.

They contribute to survival.

And they don’t just “help.” They’re relied on.

Want to see it in your house?

Then stop asking, “Is my 3-year-old ready for a butter knife?”

Start asking, “What have I actually trusted them with?”

These kids aren’t outliers. They’re what’s normal — when competence is expected, not feared.

By 4, a Child Should Be Helping Run the Household

This isn’t a stretch. It’s the human norm — before modern fragility rewrote the script.

By age 4, a child who’s been gradually included in real tasks should already be contributing in meaningful ways: fetching items, folding laundry, stirring food, helping with younger siblings. They’re not just “practicing” — they’re participating.

And with another year of repetition, trust, and responsibility, by 5, they can start carrying real weight.

Contribute to the Household

Sweep, mop, beat rugs, wipe surfaces

Fold towels, sort laundry, clean with vinegar spray

Water plants, shake out muddy boots, rinse tools outside

Manage Simple Kitchen Tasks

Crack and whisk eggs, cut fruit, stir warm dishes

Make a sandwich, serve snacks, wash produce

Use a grater or garlic press with control

Dry dishes or load/unload the dishwasher

Support Siblings and Family

Fetch diapers, wipes, bottles — without being asked

Dress a younger sibling in pull-on clothes

Feed solids to a baby with a small spoon

Calm a fussy toddler using known techniques

Supervise play while an adult is in the next room

With the right scaffolding, a 5-year-old hold the line while you shower, cook, or finish a phone call, or if you need to run out of the house they can babysit (not solo overnight or with a newborn).

That’s not unusual. It’s normal — in cultures that trust children.

Run Micro-Errands

Carry groceries from the car

Put away pantry items correctly

Bring something next door or to a neighbor

Deliver a message or fetch tools from the garage

Help With Animals or Outdoor Tasks

Feed cats, dogs, chickens — using scoops

Refill water bowls

Clean pens or cages with rags and buckets

Collect eggs, close gates, leash small pets

Respond to Simple Emergencies

Recognize distress or danger

Get an adult without panic

Know where to go or who to tell

Retrieve a phone or call for help if needed

This is what real inclusion looks like.

It doesn’t come from lectures. It comes from doing.

And no — it won’t be perfect. But that’s where focus, confidence, and grit are forged: in the trying.

Why Raise the Bar?

1. Capability is Built Through Trust — Not Time

Children don’t magically become competent at 7, 10, or 18. They become competent when they’re treated like they belong — not like they’re liabilities.

2. Respect Comes Before Protection

The safest kids around knives, fire, or tools are the ones who learned to use them early. Risk teaches caution. Sheltering teaches nothing.

3. Kids Learn by Doing, Not Watching

No toy kitchen builds real skill. But cracking eggs for dinner does.

No lecture on “helping” matches the impact of actual contribution.

4. Work Isn’t the Enemy of Childhood — Meaninglessness Is

We’ve filled childhood with stimulation and praise, but stripped it of meaning. In cultures where kids help out, they don’t need self-esteem programs. They earn it the hard way — and that’s the point.

5. Frustration Is the Forge of Growth

When a toddler fumbles with a zipper or spills the water they fetched — that’s the training ground. Real grit doesn’t come from pep talks. It comes from trying, failing, and trying again.

6. Culture Builds the Child — So Build a Better One

If kids are weak, it’s because we built a system that expects them to be. The fix isn’t more hand-holding. It’s shifting the entire frame:

From management to mentorship

From safetyism to competence

From entertainment to contribution

“But Isn’t That Dangerous?”

Helplessness is more dangerous.

Globally, young kids are trusted with sharp tools, open flames, and real tasks — and they don’t combust. They rise. Not perfectly. But progressively. That’s the point.

Final Word

If you want a capable child, stop parenting like they’re breakable.

Stop assuming "not yet" when the truth is "never tried."

Capability doesn’t come with age. It comes with exposure, repetition, and trust.

We don’t need a generation of bubble-wrapped dependents who finally “learn life skills” at 25.

We need 3-year-olds who can carry a bucket, calm a baby, and make a sandwich.

Let’s raise the bar — and raise the kids to meet it.

Postscript

There’s a full age-by-age capability guide (3 to 6) in the source document.

It’s not a checklist. It’s a wake-up call.

Let me know if you want that published as a follow-up, or broken into visuals.

What should we do if we were raised overprotected? Any way we can undo some of the harm that’s been caused? I feel like a lot of the narcissism and insecurity in the culture (and me) is due to this type of parenting.